Royal costume purple fever: how ancient people and animals died due to whim of kings

Nowadays, purple is quite common and even usual but this usual color is almost impossible to find on the flags of world countries. The only exceptions are two countries – the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua.

However, all of this indicates that purple was very rare in the past. In this material, we will talk about the sacred meaning of this color and the very tragic fate of living organisms, from which this “color of kings” was obtained in ancient times.

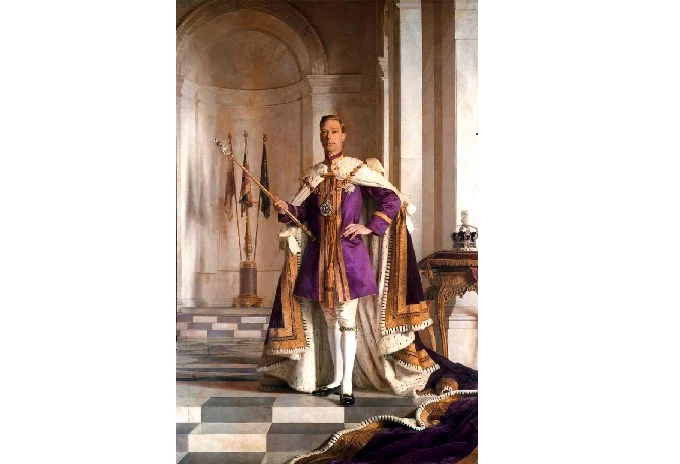

The royal “color” status

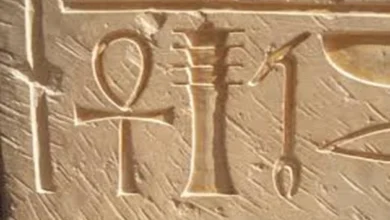

From time immemorial, purple was considered an indicator of the highest status, absolute power, and even divinity of those whose clothes had such a color. The Jewish “book of books” – the Torah – lines indicate that God himself prompted the Jews to decorate the tent where the Ark of the Covenant was kept with a purple cloth.

The great commander and emperor Alexander the Great always wore purple robes when receiving dignitaries and his vassals. In ancient and earlier eras in the Mediterranean, clergypersons, priests, high nobility, and kings wore garments of this color.

During the period of the Roman Republic (510-27 BC), free-born youths wore togas, which required the presence of a purple ribbon. Certain high-ranking officials and the victorious generals had the exclusive right to wear completely purple togas. In the subsequent imperial era of Rome, purple became associated exclusively with the color of the emperors.

Everyone, except for the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, at some times, on pain of death, was forbidden to wear purple robes. In Byzantium, this shade was firmly entrenched in the status of the imperial. So, for example, the children of the ruler Basileus who even wore purple clothes were called” Porphyrogene.”

This greatness and respect for purple in those days can be quite easily explained. This color in the ancient world was obtained from only one source – Tyrian purple. This natural dye was incredibly expensive in those days.

Beautiful, expensive, and disgusting

For the first time to produce purple dye around the 16th century BC., the Phoenicians began. Some historians suggest that the country’s very name “Phoenicia” comes from the phrase “land of purple.” The centers for the production of this dye were the coastal cities of Sidon and Tyre.

The Phoenicians received purple paint from several types of sea mollusks. The glands of these creatures secreted a valuable colored secret. To get it, there were two ways: mollusks were “milked” without causing any harm to animal organisms, or they were massively destroyed.

On the Purple Question, the Phoenicians were brutally cold-blooded. For several centuries, in the vicinity of the “purple-mining” cities, whole mounds and mountains have grown from the shells of sea mollusks. And this is not surprising – for the production of only one and a half grams of Tyrian purple dye, it was necessary to destroy about 12 thousand shellfish.

To make the scale more understandable, it is worth noting that a gram of Tyrian purple was only enough to paint the floors of one toga subtly. At the beginning of the 21st century, according to an old Phoenician recipe, such a quantity of dye was made by enthusiasts. The resulting substance (the victim of which killed 10 thousand mollusks) was estimated at 2 thousand euros.

Sources of purple in different nations

In ancient times, individual peoples obtained purple from different sources. The Phoenicians, followed by the Greeks and Romans, were made from shellfish (mollusks). The ancient historian Pliny described a recipe for obtaining Tyrian purple. So, for every 100 pounds (about 33 kg) of shellfish, about 600 grams of common salt was added.

All this was mixed and left in the open air for 3-5 days. Then the substance was continuously boiled in lead or pewter vats for 10 to 15 days until the mixture turned dark purple. Depending on the shade of the resulting dye, its price also varied. The most expensive was blackish, but they gave much less money for a color closer to red.

The ancient authors, who described the production process in their writings, noted that the finished Tyrian purple had a pronounced garlic aroma. But the smell of the mixture during the production process could hardly be called pleasant – a huge mass of rotting shellfish exuded incredible amber.

Unlike the Phoenicians, the ancient Japanese, who were also not alien to the exquisite “purple” taste, had not an animal but a plant source to obtain this color. They did not use shellfish but the root of a perennial herb, Murasaki.

The color purple was also popular among the American Indians. In southern Mexico, the Mixtec tribe is still producing natural purple dye. Mexicans get it from a clam of the Plicopurpura pansa species. However, unlike the ancient Phoenicians, animals are not killed but carefully “milked.”

Crisis of status clothing

The volumes of the ancient medieval production of Tyrian purple seriously threatened the destruction of valuable shellfish in the Mediterranean Sea. However, the war and the Ottoman Empire came to the rescue of the slugs. In 1453, during the capture of the capital of Byzantium, Constantinople, by the Turks, the Ottomans destroyed the last workshops in which they knew how to produce Tyrian purple.

After that, Europe plunged into a period of “purple withdrawal.” Kings, nobility, aristocracy, and bishops were forced to change purple robes for indigo clothes dyed with red substances (cochineal or kermes). In addition, it was possible to wear out things from the old “purple stocks carefully.”

Chemistry spares life

Ottoman expansion led to the fact that the ancient recipe for the production of purple was lost for four centuries. And when the secret was nevertheless restored, it turned out to be of no use to anyone. No, purple is by no means out of fashion and has not lost its status. It’s just that the science developing at that time played its role.

In the middle of the 19th century, malaria became one of the scourges of humankind. The European colonialists of the African continent not only suffered themselves but also brought the disease home. In 1856, a talented young chemist, William Perkin, accidentally synthesized an artificial purple dye – mauveine, while creating a cure for malaria.

Perkin, who was only 18 at the time, quickly realized the value of his discovery. The Briton immediately patented mauveine and a year later began industrial production of purple fabrics. This is how science, having revived the color of emperors, saved millions of living beings.

Nowadays, looking at purple fabric, few people think about the alterations that preceded its availability, just as they do not think about some of the things that have come to us from the distant past, considering them quite common achievements of the current civilization.