Rwandan Genocide: 5 terrible ways United Nations is to blame

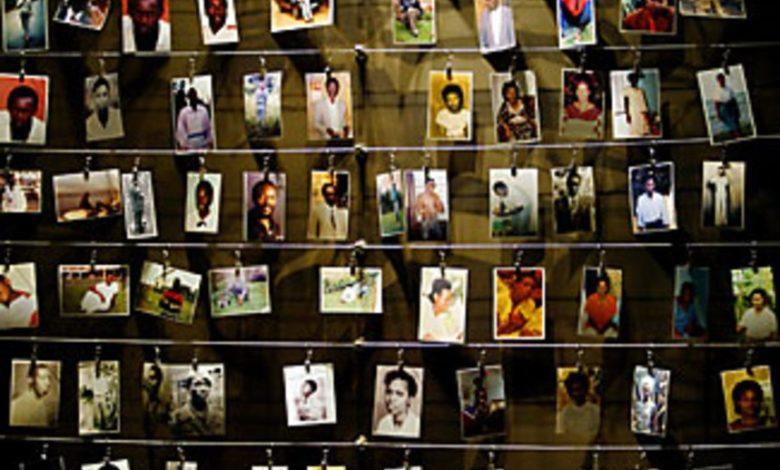

For 100 days in 1994, Hutu extremists brutally massacred 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis. It’s one of the worst genocides in the history of mankind. While it was happening, United Nations peacekeepers watched helplessly, under direct instructions not to interfere.

The whole world saw that we had failed to stop genocide – but that was just the tip of the iceberg. The dark and hidden secret of the Rwandan genocide, however, is that the nations of the UN did not merely fail to act. By selling arms and deliberately blocking international aid, the countries of the world helped Hutu extremists to commit ethnic cleansing.

Some nations did it for money, while some did it for politics, but they did it. People around the world actively helped to make genocide happen.

1. The UN Secretary-General sold arms to the Hutus

Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that the UN didn’t respond to Dallaire’s warnings. The United Nations Secretary-General at the time, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, had a vested interest in the Hutu militia. Four years earlier, he had secretly sent them a massive shipment of arms.

In 1990, Boutros Boutros-Ghali was the Egyptian Foreign Minister, and he signed an agreement with the Hutus promising to send them $26 million worth of arms. The first shipment alone, he sent the Hutus 60,000 kg of grenades, 18,000 mortar bombs and rocket launchers, two million rounds of ammunition rockets, and 4,200 assault rifles. To keep the sale of weapons secret, he labeled them “relief supplies”.

Boutros-Ghali would later justify it, saying that selling weapons was part of his job and that he didn’t think “a few thousand weapons would have changed the situation”. Boutros-Ghali, however, was more than just a passive player. He ensured that Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak sell arms to the Hutus by fighting and convincing Hosni.

When the shipment passed, the Rwandan ambassador sent Boutros-Ghali a letter of thanks. “Boutros-Ghali’s personal intervention,” he writes admiringly, “was a decisive factor in the conclusion of the arms contract.”

2. UN blocked investigations into the assassination of the President

The moment a plane carrying the Presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down from the sky, that triggered the Rwandan genocide. Two presidents were assassinated in one fell swoop, and the outrage at their deaths became the catalyst for the genocide.

The details of who shot the plane down are not entirely clear. Some people believe that the presidents were assassinated by Hutu extremists, who feared that they were about to take a soft line with the Tutsis. Others believe it was shot down under the orders of Paul Kagame, the leader of the Tutsi rebels of the RPF.

When the ethnic cleansing ended, the UN formed the ICTR – the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. A team from the ICTR, led by lawyer Michael Hourigan, began looking for who shot the plane down, and at first, the UN-supported them.

But when Hourigan found evidence suggesting that Kagame – who is now President of Rwanda – may have been behind it, his investigation was closed. ICTR Chief Prosecutor Louise Arbour instructed him to drop and stop the investigation, scared that charges against Kagame would only make matters worse.

In 2002, years later, a new chief prosecutor, Carla Del Ponte, took over the investigation and tried to reopen. As soon as she did, Carla was fired by the UN – and she’s pretty sure the U.S. and U.K. governments demanded her removal.

3. United States and France vetoed UN intervention

As the genocide began to heat up, the UN Security Council met to discuss the way forward. Hutu extremists were all over Rwandan radio, calling for the extermination of all Tutsis in the country. Thousands of people are dying every day, yet the Council was not allowed to use the word “genocide”.

The United States and France used a hidden veto to keep the world out of the conversation. They threaten to veto any action in Rwanda. They wouldn’t even let the UN use the word “genocide” in any resolution they made about it, and they used their influence to stop the UN from sending more peacekeepers.

Already planned that in advance. Richard Clarke, National Security Coordinator in the United States, as early as September 1993, wrote a note warning that UN members could vote to send more peacekeepers to Rwanda. He wanted to stay out of it. “If, as USUN reports, a Rwandan resolution has 10 votes in the UN Security Council,” Clarke wrote, “we may have to say no with a veto.”

4. France and United States withdrew UN peacekeepers

When the genocide started, about 2,000 UN peacekeepers stationed in Rwanda. That was by no means enough people to prevent it from happening, especially since they were not allowed to interfere. Roméo Dallaire repeatedly asked for more people and more power to do something about it, but he was refused. Instead, the UN withdrew most of its peacekeepers.

The declassified documents clearly show that France and the United States were behind it. On April 9th, two days after the killing began, Richard Clarke wrote an e-mail saying, “We should work with the French to get a consensus to end the UN mission”.

When they started campaigning to remove the peacekeepers, Eric Schwartz, a member of the U.S. National Security Council, tried to warn the White House about what would happen. He told them that the peacekeepers were protecting 25,000 people. If they were withdrawn, these murders would turn into large-scale genocide.

The United Nations Security Council withdrew almost all the peacekeepers from Rwanda, two days after Schwartz’s warning. The number of available personnel dropped from over 2000 to only 270.

5. White House is aware of genocide was coming

Bill Clinton visited Rwanda after the genocide, in front of a crowd of Rwandans, he expressed his regret that he had not done more. He justified his inaction, however, by telling the crowd that he “did not fully appreciate the depth and speed with which you were engulfed by this unimaginable terror.”

The declassified documents that were sent to the White House, however, tell a different story. The United States had more than just an idea that something terrible was going to happen – they knew that the Hutus were planning genocide before it began.

Bill Clinton was informed, Sixteen days before the killings started, that the Hutus had planned a “final solution to eliminate all Tutsis”. He received regular reports of this, each using the word “genocide” to describe their plan, and he received details that, even in retrospect, were incredibly accurate.

The U.S. is aware of precisely what was going to happen more than two weeks before it began but made a conscious decision not to get involved. Rwanda, they decided, was of no value to American interests. “Whether we get involved in one of the world’s ethnic conflicts,” Clinton said, justifying his decision, “must depend on the cumulative weight of American interests at stake.”